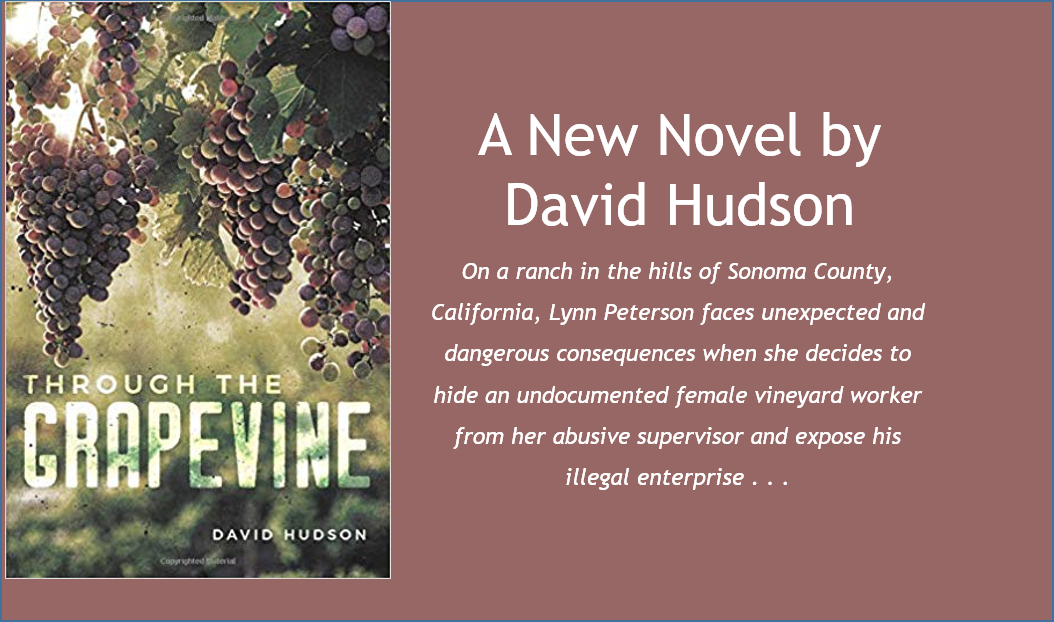

Why I Wrote This Book

The Sonoma landscape has fascinated me for years–the rugged coastline, the Russian River Valley, the redwoods–but it was the high, remote ridgetops north of the river–a world apart–that captivated me a few years ago and compelled me to write this story about women standing up to powerful forces with determination and courage–and place it there.

Below is a sampling from Chapter One, The Fugitive.

Chapter One

The Fugitive

Lynn Peterson pulled the covers up against the chill of an early August morning on the ridgetop, a thousand feet above the valley floor. She squinted toward the window. A rooster crowed. She closed her eyes, scrunched into the mattress for one last decadent moment, and swung her feet to the floor. She reached for her clothes on the chair beside the bed and watched the sky lighten as she pulled on worn jeans, her favorite chamois cloth shirt, soft against her skin, and a non-descript gray sweatshirt

She crossed the hall to the kitchen, filled an insulated mug from a programmable coffee maker, and stepped out onto the porch that spanned the front of the house, into the new morning. A faint breeze stirred the wind chime hanging from the metal roof. She sipped her steaming coffee and breathed long and slow, inhaling the moist fragrance of earth and grass and evergreens. Waking birds welcomed her from the trees across the road that glowed where golden light poured down on them like syrup. On the western horizon a thin blue line brightened—the vast Pacific Ocean.

Lynn walked behind the house toward the barn. Stopping short, she tilted her ear toward the pasture below it and beyond, to a mechanical hum, just discernible. A car approaching from the south, a half mile or more down the road, surprised her, grew louder. “Who could be coming up here this early?” she wondered. “And why so fast?”

Chickens clucked when she opened the door of the old barn, which had stood since the ranch’s earliest days in the 1890s, its rough, unpainted siding a rich, weathered gray, its metal roof—once a glittery silver—now rusty red. The interior was cool and dark, suffused with rich aromas of hay and manure, barnyard animals, and ancient unfinished wood. She smiled and stroked the door frame beside her, as if to absorb the earthiness, authenticity, and unapologetic simplicity of the place. Then she flipped on the light and began her rounds, swinging open the big east-facing doors, letting the bright, young daylight in and the chickens out.

The hum had become a roar. Drawn by it, she stepped outside. The car crested the rise just beyond the big metal equipment barn, too fast, she thought. Where’s it going in such a hurry? What? Instead of speeding on by it slowed at the big oak and turned into the drive, dust washing over it as it came to a stop in front of the house.

She walked toward it. The driver stepped out of the car. There was no mistaking her friend Karen Boyd, the nurse. She was Native American, Dakota Sioux, sixtyish, of average height and build, bearing the weight gain of age. Her brown skin glowed. Long silver hair flowed over her shoulders. High on her left cheekbone, beside and just below the eye, she bore a small tattoo, a light, faded blue—a bird in flight.

Karen walked around the car and opened the door for her passenger, who lay slumped in her seat, head down, staring at the floor. The woman eased out of the car and stood expressionless—blank-faced. She was a youthful-looking middle-aged Latina with a pretty face—strong jaw, high cheekbones, petite nose—long dark hair.

“Lynn,” Karen said, “I’m sorry it’s so early, but this is important.”

Her tone brought Lynn to full attention.

Holding her passenger by the arm, she said, “This is Teresa, a friend of mine. She’s had a rough time of it. She was attacked last night at work, raped. It’s a mess. We need help.”